The Corte program supposes an interruption in the usual programming of Artnueve in order to host a specific project by a guest artist, thus enriching the contextualization of the gallery project and showing new perspectives on the artistic event. In this way, it establishes a stimulating strategy to deepen the work of artists or creatives, with different discourses and disciplines, but who have found in art that place to reflect on contemporary problems.

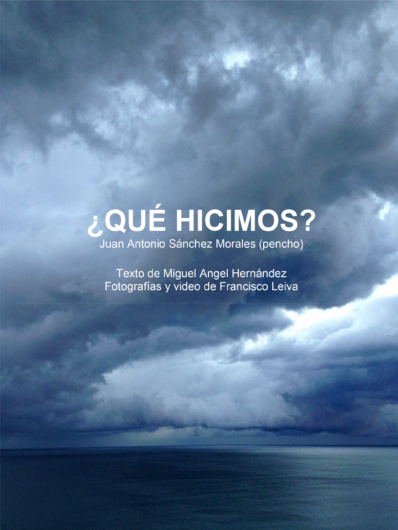

On this occasion “What we did” is the proposal of the architect Juan Antonio Sánchez Morales, who has proposed an intervention for the gallery, in which he reflects on climate change and the impact and transformations that this will have on both the landscape and the society.

Resonances

Miguel Ángel Hernández.

In his study of Walter Benjamin’s concept of history, Michael Löwy finds a figure that sums up the German philosopher’s thought at a stroke: the “fire warning”. For Löwy, Benjamin, the first to see the fire, was ahead of his time and knew how to name the catastrophe. Not only the warlike and political catastrophe that was about to devastate Europe, but a greater catastrophe, that of a way of life sustained by progress as a debris-generating machine. This threat, according to his vision, was not located in the future to come, but nested in all the layers of the present. “That this continues to happen – he wrote – is the real catastrophe.”

Löwy regrets that no one listened to Benjamin, as if his voice – like that of some others – spoke at a time not yet ready to understand the power and urgency of his warning, or as if he were cursed, condemned, like the prophetess Cassandra, not to be believed at any time.

Although almost eighty years separate us from his criticism of progress, we continue without listening to the warnings, the warnings of fire or overflow, closing our eyes and ears, looking away, disbelieving words, images and even facts. It does not matter how many times we are told about the urgency of transforming our way of life, it does not matter how many times we see it, that we understand it, it does not matter that we have even begun to check it. For some strange reason, these certainties do not just move us into action, they do not vibrate in us, they do not end up resounding. And this may be the real tragedy.

In his recent critique of the characteristic acceleration of modernity, the sociologist Hartmut Rosa has proposed an alternative to that runaway time that is moving mercilessly forward. For Rosa, in the face of acceleration, we need “resonance”. To return to a connection between the subjects, a vibration also in the tonality of what surrounds us. To resonate, he says, is to pace oneself, to allow oneself to be touched, not to impose, it is to retake the lost link with the subjects, objects and the environment.

The artistic space is precisely one of the places where that resonance takes place, where that transforming vibration acts, the context where what is said and seen “resonates”, where what is silenced and invisible has the ability to be heard and shown, where the “notice of fire ”tinkles and the alarm goes through the body.

The work of Juan Antonio Sánchez Morales displays this logic of resonance. The images, the words, the data, but also the way they are arranged in space and surround us, visualize the catastrophe to come – at least one of them, the great overflow – and generate in the viewer a sense of urgency through a clash of times: the adverse future that is already here, and the ruinous present already tinged with the past. Perhaps that is one of the most urgent functions of art in our days: to show – rehearse, trace, glimpse – the future of the present, make it resonate, and above all create the space and conditions for words and images to vibrate, act, transform.